The regulation of public health data collection and display is an interesting field of research for historians of contemporary public health. Here’s how I came to think about it:

On our way back to Copenhagen from three days of vacation on the island of Öland off the coast of SE Sweden with its beautiful and peculiar landscape (especially the alvar heath), we took a short break in Kristianopel, once (in the early 17th century) an important and heavily fortified Danish border town, now a tranquil vacation resort.

On our way back to Copenhagen from three days of vacation on the island of Öland off the coast of SE Sweden with its beautiful and peculiar landscape (especially the alvar heath), we took a short break in Kristianopel, once (in the early 17th century) an important and heavily fortified Danish border town, now a tranquil vacation resort.

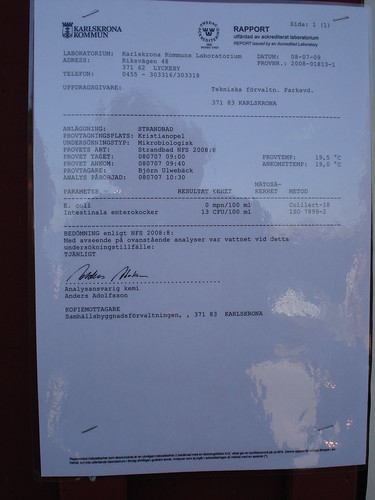

While Anna went down to the beach to take a swim in the Baltic Sea, I took a closer look at the local billboard where I found, among announcements for local flea markets and invitations to parties for young church-goers, an official report on the bathing water quality issued two days earlier by an accredited laboratory:

saying:

- E. coli: 0 mpn/100 ml, measured by the Colilert-18 method

- Intestinal enterococci: 13 CFU/100 ml, measured according to ISO 7899-2

Zero E.coli is fine, of course, but 13 CFU (colony forming units) of enterococci (common faeces bacteria) is not so good. Wikipedia informs me that the state of Hawaii accepts only 7 CFU/100 ml before posting warnings! The municipality of Karlskrona, however, concludes that the water quality is “tjänlig” (suitable).

I’m probably about the only person visiting Kristianopel who has ever cared to read, let alone understood, the water quality report. Regulations issued by the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency stipulate that local authorities must make such tests (see Naturvårdsverkets författningssamling 2008:8) and make them publicly available. But apparently the local authorities don’t have to announce the results in a way that makes sense to visitors to the beach—for example that the Kristianopel water is twice as bad as what they accept in Honolulu.

Well, Anna didn’t catch any nasty bugs and the rest is for the Kristianopolitians to consider further. But that said, I think their water quality report raises an interesting general issue. Ground-level ozone, pollen levels, etc. are heavily displayed on TV, in newspapers, etc.; for example, the National Museum of Natural History in Sweden issues a daily pollen prognosis report on the web. What other kinds of public health data are displayed in public? How are these data displayed? Through which media? And which are the political processes behind the decisions to have such data collected and broadcasted to the public?

In fact, the history of public health could be understood (cf. Dorothy Porter’s Health, Civilization and the State: A History of Public Health From Ancient to Modern Times, 1998; read a good review here) as the continuous political negotation of such data and their public display.